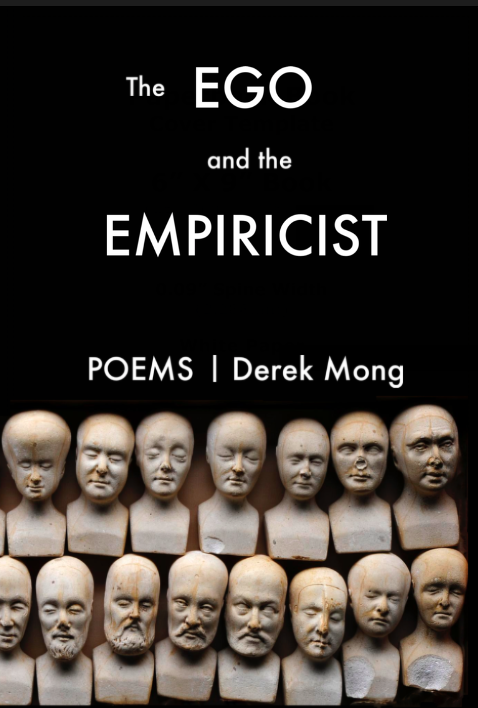

The Ego and the Empiricist by Derek Mong is the finalist for the Two Sylvias Press Chapbook Prize.

Praise for The Ego and the Empiricist:

"Whatever I take from this forest floor," writes Derek Mong in this gorgeous new chapbook, "I borrow." And, true to this statement, Mong adeptly gathers a wide swath of source material and produces poems that honor their origins, spring off from them, and, ultimately, give back. As Mong explores the journey of the body over time, his lines are both charged and solemn, with turns of phrase at once unpredictable and spot-on. This is a haunting, riveting collection.

— Natalie Shapero

A reader can open any contemporary journal of poetry and quickly pick up characteristics of the current mode. If the magazine is serious you’ll also find good poems, and many more bad ones, and what falls between—the largest group. In this our age is like any other. Derek Mong’s The Ego and the Empiricist, though its music is very much of our moment, takes as starting point poems and poets distant in time and worldview, and from first poem to last the difference is stunning. Mong has made of original medieval and renaissance works a grouping of wholly transformed new poems that sound contemporary, but retain the urgent intimacy of un-ironic spiritual “exercises,” as the Jesuits might have it. As I read I began to think of these poems as a new species of retablos, with verbal objects in the place of iconic imagery. There is the same naïve, unmediated closeness of address to Christ—“You’re smoke, you’re/ thunder’s anti-static rope,” the same heuristic feel to the pieces, as if intentionally made for devotional purposes. How strange! Not since Lowell’s Imitations ( which Mong acknowledges in his notes) have we had a grouping of poems so alien in tone and tilt to the current secular mind brought into contemporary American idiom, fully alive, fully human. And human they are; these are not the words of the elevated or pious: “Still, I can’t explain my fear/ of flies, nor the time I beat a man for smiling.” There is everywhere an offhand grace, “Later a green glow, like the inside of a swept cape,/ hung where the sun crossed the bay,” coupled always with the modesty of a true religious—“I am still building a theory for just what that means.” I can hardly say how much I like these poems, which are shocking for all the unusual reasons.

— Jeffrey Skinner

A poetry of transformation, The Ego and the Empiricist blurs the space between translation and homage, and shapes a free-ranging and symphonic landscape populated by monks, farmers, philosophers, bees, and all manner of amazements. In making lost voices come alive again, Derek Mong demonstrates the poet's most profound skill: the gift of speaking in tongues.

— Ann Townsend

Sample Poem:

In the Shadow of a Scrivener’s Quill

Over the O, the ah, the fable’s lazy start, its Once

Upon a Time; over the gild-work and into the text block, past

the signatures and spine; over the names

remaindered from distant shores which you swept

up and relined; over the we, the she, the I; over

the cattle carts clacking on cobblestones,

dead prayers, lost plays, gun-free melees,

and the other sounds those foreign consonants retain--

over the footnotes, toward the fore edge, through

the marginalia that’s raining down the vellum’s white,

inviting frame; over the gaps which absent words

plant into the lines; over the cloth

that holds your place; over the ink that’s dried;

over the flesh and under the hide of enough

animals it’s said whole herds passed

through your hands; over the grooves

your newest word still shines inside, past the pages

bound face-to-face, revised; over the stories,

all the oldest ones, which—like light we skim

from distant stars—renders our hurtling less lonely;

over the eons, inside the authors, onto an easel

and into your inkwell, the shadow of your scrivener’s quill

is dancing, dark foot dipped into a darker pool, it lifts

a load of sweet, unfiltered evening

then lands, black dash to reattach the past,

and coax us up the learning curve we climb

by generations. O monk or scribe

who curled his back inside candlelight, I’ve often

questioned your motives: did penitence push

you to push books into the dark beyond--

stepping stones you leapt toward St. Peter’s ledger--

or was scribe work just an exercise in exercising options?

Take that candle for life’s defining metaphor

and the tomes you shelve begin

to resemble heaven. Perhaps you were seduced

enough to change them, as when chaperones

left alone too long imagine misbehaving?

Or did anonymity only remind you

of the pleasures it offered in compensation: to live

for months inside Homer’s head, bundled

up in one-word increments; to touch the word

of God, put it down in red, before returning

to a relay team that runs for centuries

untended? One day our world will call you up

again, place into your hands our scraps

of self, and ask you to arrange the parts

that make us sharp, redeeming. For now may you

swim inside our memory, rippling unnoticed.