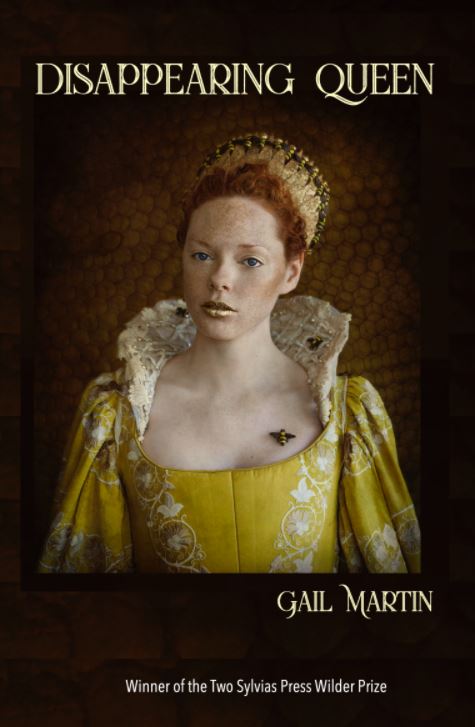

Praise for Disappearing Queen (Winner of the 2019 Two Sylvias Press Wilder Prize):

The poems of Disappearing Queen emerge from the consciousness of a woman who has been on the planet long enough to know the bliss and price of embodiment. “O body,” Martin writes. “You are a fickle clock.” Echoing the tropes of Plath’s bee poems (“I have a self / to recover”) but also extending Plath’s timeline into cronedom (“wonder if I can learn to chew years / into gold”), Martin writes with bold candor about the era of life when the vacations are cold, bones implode, and one faces the atrophy of joy. Her directness is frontal and devastating: “I write for death. Why not make it explicit?” Yes, there is elegy here, the Lot’s wife act of looking back, but not gloom. Maybe the antidote to gloom is ferocity, “to show some backbone as I’m being dethroned,” and wit: “The surgeon tells me I’m deteriorating right / on schedule.” There is even a wedding, a birth, but no easy resolution to a queendom that offers more responsibility than power. “Is there any queen at all in it?” she asks. If this gorgeous, clear-sighted book offers an answer, it is yes—the queen is poetry as Gail Martin practices it, even as she documents, with lyric intensity, her shimmering disappearance.

~Diane Seuss, author of frank: sonnets, Four-Legged Girl, and Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl

Gail Martin’s marvelous book Disappearing Queen resurrects the beloved and difficult dead—a colossal task for such small things as poems to accomplish, but take my word for it, she does it. In fact, her constituency is the dead, and the pre-dead, the pre-lost—which is to say—us—all of us. In a tough, ironical, celebratory, gimlet-eyed, and lamenting voice, Martin describes the rhythmic creation and destruction of everything, especially our poor bodies, in such precise ways that I kept murmuring that’s it, that’s it. Martin’s personal history, with its tenderly and acerbically drawn characters, with weddings leading inevitably to funerals, becomes a universal history, a tidal pool filling and emptying. But with danger, lots of danger, as things are torn away with or without anesthesia, and with surprise, and startlingly fresh juxtapositions. If like me you need a companion through The Great Changes, Gail Martin is your poet.

~Patrick Donnelly, author of Little-Known Operas, Nocturnes of the Brothel of Ruin, and The Charge

The poems of Disappearing Queen emerge from the consciousness of a woman who has been on the planet long enough to know the bliss and price of embodiment. “O body,” Martin writes. “You are a fickle clock.” Echoing the tropes of Plath’s bee poems (“I have a self / to recover”) but also extending Plath’s timeline into cronedom (“wonder if I can learn to chew years / into gold”), Martin writes with bold candor about the era of life when the vacations are cold, bones implode, and one faces the atrophy of joy. Her directness is frontal and devastating: “I write for death. Why not make it explicit?” Yes, there is elegy here, the Lot’s wife act of looking back, but not gloom. Maybe the antidote to gloom is ferocity, “to show some backbone as I’m being dethroned,” and wit: “The surgeon tells me I’m deteriorating right / on schedule.” There is even a wedding, a birth, but no easy resolution to a queendom that offers more responsibility than power. “Is there any queen at all in it?” she asks. If this gorgeous, clear-sighted book offers an answer, it is yes—the queen is poetry as Gail Martin practices it, even as she documents, with lyric intensity, her shimmering disappearance.

~Diane Seuss, author of frank: sonnets, Four-Legged Girl, and Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl

Gail Martin’s marvelous book Disappearing Queen resurrects the beloved and difficult dead—a colossal task for such small things as poems to accomplish, but take my word for it, she does it. In fact, her constituency is the dead, and the pre-dead, the pre-lost—which is to say—us—all of us. In a tough, ironical, celebratory, gimlet-eyed, and lamenting voice, Martin describes the rhythmic creation and destruction of everything, especially our poor bodies, in such precise ways that I kept murmuring that’s it, that’s it. Martin’s personal history, with its tenderly and acerbically drawn characters, with weddings leading inevitably to funerals, becomes a universal history, a tidal pool filling and emptying. But with danger, lots of danger, as things are torn away with or without anesthesia, and with surprise, and startlingly fresh juxtapositions. If like me you need a companion through The Great Changes, Gail Martin is your poet.

~Patrick Donnelly, author of Little-Known Operas, Nocturnes of the Brothel of Ruin, and The Charge

Sample Poem:

THE WORLD WE WANTED SHONE SO BRIEFLY

Real life was finally about to begin.

Remember the romance of the silver cigarette case

in college? The integrity of your firstborn’s eyelashes?

We discarded alternate destinies like tired cards

in the Flinch deck. We were only looking forward.

Of course, like the teeth of beavers and horses, there

are parts of the past that never stop growing.

Garage - tree house - vacant lot kinds of cruelty--

how we took turns being mean.

And later, some serrated evenings, dinners

of bluster and recoil, dodge. Flowers sent

or not sent to someone’s funeral.

Mostly there are the years you watch

your neighbors’ cars slide in and out of their garage.

Between blue herons and tumors, you change

the sheets.

We were all surprised to find ourselves old

but really the signs were everywhere, and we

acknowledge we’d been told. Name one

important thing that has not already happened.

THE WORLD WE WANTED SHONE SO BRIEFLY

Real life was finally about to begin.

Remember the romance of the silver cigarette case

in college? The integrity of your firstborn’s eyelashes?

We discarded alternate destinies like tired cards

in the Flinch deck. We were only looking forward.

Of course, like the teeth of beavers and horses, there

are parts of the past that never stop growing.

Garage - tree house - vacant lot kinds of cruelty--

how we took turns being mean.

And later, some serrated evenings, dinners

of bluster and recoil, dodge. Flowers sent

or not sent to someone’s funeral.

Mostly there are the years you watch

your neighbors’ cars slide in and out of their garage.

Between blue herons and tumors, you change

the sheets.

We were all surprised to find ourselves old

but really the signs were everywhere, and we

acknowledge we’d been told. Name one

important thing that has not already happened.